The darkness was all-consuming as we reached the midpoint of our journey, blackness and confusion all around. It had already taken us two days to make it to the forest. At a certain point, we looked up and realised our child was no longer with us, lost amid the shimmering foliage. “Teddy, where are you?” my wife called. “Forget him, he was only slowing us down,” I murmured, perceiving the dim shape of a branch through the leaves.

But there is always a way through – if not the colour, then the shape will guide you. Backs aching, eyes narrowing, language stripped to pure function, we began to piece together the blackest sections of the puzzle. “This is a waste of life,” my wife eventually concluded and returned to her novel. The glory would be mine alone. By midnight on the eighth day, the 500-piece Super-3D holographic jigsaw of the Hogwarts Express was complete.

Yes, this was technically a sixth birthday present for our Harry Potter-mad son. Yes, we did most of it while he watched Netflix. Yes, I’m aware 500 pieces is not that many. Yes, this was a decadent amount of time to work on something so pointless. But sometimes, pointlessness is precisely the point.

At any rate, we are far from being the only household that has turned to jigsaws in lockdown. Decent 1,000- piecers are harder to find than yeast these days. Gibsons, one of the UK’s leading jigsaw companies, reports a year-on-year sales increase of 132%. “We’re doing Christmas-level sales,” says marketing manager Samantha Goodburn. “We’re doing our best to print out as many as we can and get them out to people who need them.”

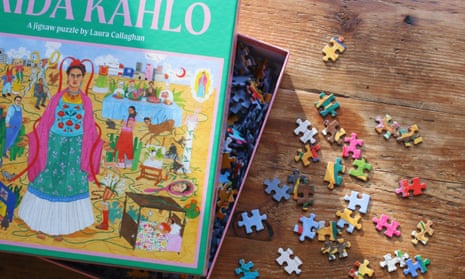

John Lewis is almost puzzled dry. Among its best sellers are The World of Frida Kahlo by Laurence King and Rainbow Hand by Galison. The satirical montage artist Cold War Steve has one, too, inspired by The Festival of Brexit – but this too has sold out. Wentworth, the Wiltshire-based company whose wooden fine art puzzles are highly prized by collectors, has nothing over 250 pieces.

But puzzle junkies no longer care where they score their hit. “I don’t think I’d buy one of those super-twee ones of a country cottage or anything,” says Liz Vater, director of the Stoke Newington Literary Festival, who has completed four puzzles since lockdown, including a David Bowie-themed moon scene. “But if someone gave me one like that, I don’t think it would matter.” The experience is common. Jigsaws are a gateway drug to twee. You start out on a nice New Yorker cover. Soon, it’s Teddy Bears & Tricycles.

“You don’t want masses of sky or sand,” says my Granny Rose, 90, and a lifelong puzzler. “You want it to be interesting.” She grew up on jigsaws – her father only let her and her sister look at the picture once – and usually has one on the go. She likes doing them with friends or family, but in lockdown, she is on her own, working on an image of Blackpool beach that a friend dropped round. “It’s ghastly!” she laughs. “But my other jigsaws are in a high cupboard and I don’t want to risk climbing up on a chair.”

It’s not too hard to see why we’re reaching for jigsaws. Margaret Drabble wrote a memoir inspired by puzzles, The Pattern in the Carpet: A Personal History With Jigsaws. “They provide hours of painless social intercourse or moments of peaceful, solitary retreat,” she wrote. “They give you an illusion of order and progress when all around is chaos.” There is such a thing as competitive puzzling, but this is not the point, Drabble argued. Here is a “harmonious, constructive, co-operative activity, free of the rivalry that makes so many games contentious and so many children so cross.” And if you want to do it on your own, while listening to a podcast or the birds singing, that’s fine, too.

There have been studies into the cognitive effects of jigsaws. One concluded that the activity “recruits multiple visuospatial cognitive abilities and is a protective factor for visuospatial cognitive aging”. But it’s possible to overthink this. Dr Abigael San of the British Psychological Society sees it as a classic mindful activity. “Focusing on detail, taking the time to relax, having an aim without pressure – all of those things are beneficial and a counter to the wider anxiety that people are feeling at the moment. It gives you a sense of control in a chaotic situation. The world is unpredictable, whereas a jigsaw puzzle is certain.” As long as no one has lost a piece.

The jigsaw is thought to have been invented in 1766 by John Spilsbury, an engraver and mapmaker whose “dissected maps” were used to teach. Jane Austen included a jigsaw in Mansfield Park (1814). The Bertram children laugh at poor cousin Fanny as she is not familiar with these fashionable toys. Adult puzzles emerged in the 20th century. At first all the pieces had straight edges. My granny remembers the “two spinsters” who lived next door to her had one like this – finally completed by the evacuee who came to stay during the war. She also remembers dedicated jigsaw libraries – of which I can find only one in England, based in a Baptist church in Exeter. Social distancing has forced it to close during lockdown. “Our clientele is usually quite elderly – people with time on their hands,” says its chairperson, Susan Hazemore. “It’s good for their eye-hand co-ordination. We have a few people who suffer from dementia and also insomnia, too. I don’t think we’ll be open until at least September now, but I am hoping that when I can go out and about a bit, I can do some delivering to people who are on our books.”

For many, lockdown has been a foretaste of retirement. “Life doesn’t usually warrant a 1,000-piece jigsaw,” says Liz Vater – who realised she would have to cancel her literary festival early on and so found herself with time on her hands. “At the beginning, I had so many plans,” she says. “I was going to read all the books I have around the house. And I just wasn’t able to read. It was horrible. I always have a book on the go. But then I started a jigsaw. It does a similar thing. I was focusing in. It was quite meditative. I was processing as I was going. I’ve loved the endless hours just focusing on one task, searching for pieces defined by colour, perspective or shape.”

One thing we have learned is that global catastrophes don’t introduce brand new ideas, what they do is accelerate ones that were already floating around the ether: universal basic income; modern monetary theory; jigsaw puzzles. When I interviewed Sir Patrick Stewart in Los Angeles three years ago, he was adamant that jigsaws were about to become the new “adult colouring books”. We were supposed to be talking about some superhero movie he was in, but he was more interested in telling me about the Picasso chair he was piecing together. “At first I was a little embarrassed about it, as it was something I’d done as a kid,” he told me. “But when I would occasionally mention it, people would whisper: ‘Oh, you do jigsaw puzzles, too? What kind? How many pieces?’ It’s like a secret society.”

Goodburn of Gibsons says that jigsaws have been on a steady uptick since she joined the firm five years ago. There is a jigsaw emoji. Jigsaws were also added to the Consumer Price Index used to measure inflation in 2017 (alongside gin and almond milk). “It pre-dates coronavirus,” she says. “It’s part of the trend of looking after yourself, being more mindful, taking a digital detox.” Nostalgia is popular across age groups – one of their bestsellers is called 1980s Sweet Memories, a montage of Marathons, Opal Fruits and Jelly Tots – but they have also commissioned a new range of design-led jigsaws with a hipper audience in mind. “We have one called Avocado Park. It’s just a load of cartoon avocados having a great time in a park.”

You can tell a lot about a nation by its jigsaw designs. Cats are popular. So are Spitfires. And the manically detailed, Union Jack-filled designs that Gibsons commissions often veer close to the sort of art you can imagine coming out of a Faragist dictatorship. Populist Realist Art? I ask the Observer’s art critic Laura Cumming for her verdict on The Airshow, which shows gleeful picnickers beneath a sky heavy with warplanes. She professes herself a little baffled. “The vintage planes would scalp the day-trippers, the photo-real detail seems bizarrely mismatched with the graphic kitsch and it is very strange that the hardest part of a jigsaw – long stretches of barely differentiated colour, such as sand, sea or sky – are eliminated as if the artist wanted the experience to be quick and easy. Is the idea to get through them as fast as possible and buy the next?” She reckons Pieter Bruegel the Elder is a good jigsaw artist as “you enter so intimately into his mind, piece by piece; but I think Seurat is the most beautiful to do, half a dot, a whole dot, etc, as you get a deep sense of his colour alchemies. The worst I’ve ever had to do, in company with my aunt, was Renoir’s Bal du Moulin de la Galette, where every stroke melted into another.”

I turn to Steve Crisp, one of the UK’s most in-demand jigsaw illustrators. “I’ll sort of do half a painting before moving on to computer, where it’s easier to move things around,” he explains. “The brief is basically, make every area of the puzzle interesting. Make sure there’s no area with too much foliage or blue sky. At the very least, there’ll be birds everywhere. I kind of pack it in.”

At the moment, he’s working on a 1950s toy shop, a pop festival and a summer camp for an American company. It’s varied, but it’s always escapist. “A lot of people say when I do an image: ‘I’d like to live there,’” he says. “That’s the aim – to get that feeling for people. Hoping everything’s fine and lovely. I mean, we all like that, don’t we?”